Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

• Intriguing book digitalized for online reading: Barrington's New London Spy for 1809, or, The Frauds of London Detected.

• Which came first: the product or the L'eggs?

• Smoking little Josiah: mandatory fumigating with brimstone against smallpox in 1775 Boston.

• Amelia Earhart's cautiously optimistic advice to an aspiring female pilot in 1933.

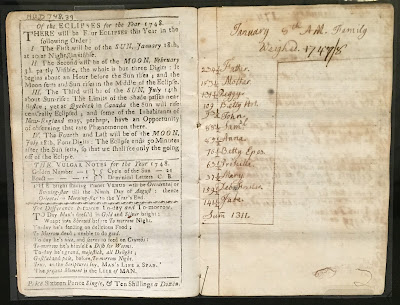

• Looking closely at a young New York woman's early 19thc. diary.

• Image: Another needlework pattern - for aprons or neckerchiefs - from the Lady's Magazine, 1786.

• Posthumous portraiture in 19thc. America.

• The unexpected beauty to be found in America's last surviving textile mills.

• Remains of an early African-American burial ground discovered in NYC beneath a Harlem bus station.

• Lustful looks: signs of venery in John Ward's 17thc diaries.

• Image: The Swell's Night Guide to the Bowers of Venus.

• Brighten up a dull winter day by carrying a little bouquet of bright flowers in this 19thc silver holder.

• Mr. A. Watkins and the touring bee van.

• Why (and how) does an 18thc fictional character have a grave in the cemetery of NYC's Trinity Church?

• Ranch dressing: what to wear to a dude ranch in the 1930s.

• Image: Tudor rose, Canterbury Cathedral.

• A mysterious ritual burial for two horses killed serving in the War of 1812.

• The arches of Madison Square Park in New York.

• Paper dolls and ready-to-wear brought flapper fashions to the masses in the 1920s.

• Monsters and moral panic in 18th-19thc London.

• The kitchen is the heart of the home: why these two slave cabins matter.

• Image: When you want to fight, but your horses just want to hug it out.

• Life in the King's Bench Prison.

• What they left behind: things people keep to remember their deceased loved ones.

• Somewhere between history and style: the eccentric beauty of Malplaquet House.

• Just for fun: "When you're rich, and when you're poor" from Mad Magazine, 1977, and still too true.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Laws Concerning Women in 1th-Century Georgia

1 year ago

One of us --

One of us --